By Graham Sweeney

Editor

Despite diminishing most of his ability to hear, fighter planes provided Col. Elmer Follis Jr. a life stocked with purpose, valor and honor.

As a pilot for the U.S. Air Force, Follis flew 400 combat missions in the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

Many of these missions were flown in his F-100 Super Sabre nicknamed Full House, which he speaks about like an old friend.

A diminutive teenager, Follis was told his senior year of high school that he wasn’t athletic enough to complete boot camp for the Marine Corps. However, he proved everyone wrong.

“They said they didn’t want runts and did everything they could to wash me out,” he remembered. “But I persevered and made it through. I never gave up.”

After completing boot camp and technical training, Follis, 88, served as an aviation mechanic in North Carolina.

While immersed in the maintenance side of aviation, he became deeply interested in becoming a pilot.

“I saw those planes coming and going (from the air station),” he noted. “And I said, ‘I don’t want to work on them, I want to fly them!’”

After receiving his discharge from the Marines in 1947, Follis returned home to civilian life in Memphis, where he got a job with Chicago & Southern Airlines to stay close to aviation. He gained flight instruction with benefits from the G.I. Bill and received his private license at the age of 19.

In 1951, he entered the U.S. Air Force Aviation Cadet Program and received basic training on the T-6 aircraft in Mississippi. He was the first student in his class to solo. He would go on to complete advanced training in the F-51 Mustang in Alabama and received his pilot wings in 1952.

It was during the formation phase of training that he experienced one of his “greatest thrills” by flying with aviation legend Chuck Yeager.

“He flew in our four-ship formation,” Follis said of his role model. “He was on my wing.”

Five years earlier, Yeager was the first pilot confirmed to have exceeded the speed of sound in level flight.

After receiving jet upgrading and fighter bombing training in the F-80 Shooting Star, Follis reported to Kimpo Air Base in Korea where he flew 100 missions with a tactical reconnaissance squadron.

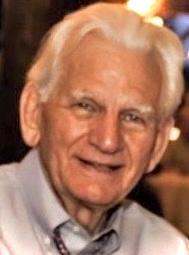

Photo by Graham Sweeney

Col. Elmer Follis looks at old photos, certificates and awards while reminiscing about the more than three decades he spent in the United States Air Force. Follis, 88, retired from the service in 1982 after playing major roles in the Korean War and Vietnam. He flew 400 combat missions. After retiring, he graduated Suma Cum Laude from the University of Memphis.

Most of his missions consisted of photo reconnaissance in unarmed aircraft deep in enemy territory. Some of the missions were flown along the Manchurian border and required an armed escort due to encounters with enemy MiG fighters.

While in Korea, President Dwight Eisenhower selected Follis to brief him on the specifics of his mission accomplishments.

“This was the man responsible for winning World War II,” he said. “A genius, asking me about my plane.”

After the Korean War, Follis scored particularly high marks on his evaluation exam and was selected to be an teacher at the Air Force Flight Instruction School in Alabama.

In 1957, Follis was assigned to the 18th Tactical Fighter Wing in Okinawa. There, he became certified as a nuclear bomb commander in the F-100 Super Sabre and sat “nuclear alert” with weapons more powerful than those used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 12 years earlier.

“We were considered American kamikazes,” he said. “These missions were considered to be ‘one-way’ because of the great distances to the target. There was enough fuel to reach the target, deliver the weapon and exit but not to return to base.”

It was never necessary for the pilots to complete a mission of this magnitude, but Follis can recall the significance of being on nuclear alert.

“There were nights we bunked next to the planes on the landing strip,” he said. “We had to be ready if we got the call. That’s a hell of a feeling.”

In 1960, Follis was assigned to a squadron in South Carolina that participated in numerous ocean crossings to Europe and the Middle East. He performed extensive temporary duty tours to Italy and Turkey, where he again had to sit nuclear alert.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, his squadron was deployed to southern Florida, where they assumed “quick reaction alert posture.”

As squadron operations officer, Follis would have led the first strike against a Cuba target, the San Cristobal guided missile site.

In 1967, Follis was transferred to Vietnam and assigned to a F-100 squadron as operations officer. There, he flew 300 combat missions.

The three most common missions he flew were close air support, interdiction and landing zone preparation for friendly helicopters.

Follis estimates that his squadron saved thousands of U.S. lives providing air support to ground troops.

He said he often ponders the generations of lives that have been impacted by the soldiers he was able to protect.

“We saved a lot of lives,” he recalled. “Just think, if those men had died, they wouldn’t have gone on to have children and so on.”

One particular instance, which earned Follis his fifth Distinguished Flying Cross, was during the Battle of Dak To, when friendly forces were in imminent danger of being overrun.

During the battle, Follis, who was praised and honored for his accuracy throughout his military career, was asked to deliver bombs much closer to friendly forces than normal.

“We had to drop 750-pound bombs only 70 meters from our forces,” he said. “That is less than half of the recommended safe-separation distance.”

After the battle, Follis received glowing praise from members of the Army’s ground forces, as air power accounted for “at least 70 percent” of the North Vietnamese Army casualties.

After Vietnam, Follis was assigned to Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas and named director of operations for the 80th Flying Training Wing.

He then became director of operations and plans for NATO in Izmir, Turkey.

After that he became chief of the Nuclear Branch at Allied Forces Central Europe where ha was responsible for the implementation of the nuclear, biological and chemical policies in NATO’s central region.

“I still can’t talk about a lot of what we did,” he said, referring to the classified nature of the job.

Normally a three-year assignment, NATO extended him for two additional years because of his outstanding performance.

After retiring in 1982, Follis returned to college and graduated Suma Cum Laude from the University of Memphis.

As a civilian, Follis worked as the director of safety, environmental services and mail services for Methodist Hospitals of Memphis.

He currently enjoys giving speeches and talks at meetings hosted by Kiwanis Clubs, the Salvation Army Adult Rehabilitation Center, Daughters of the American Revolution, Forever Young, etc.

“You have to stay active,” he said. “That’s how I’ve always lived.”